The “Nest:” the Birthplace of Perception

One morning as I went out to work in my flower bed, I found a baby robin hopping about the front yard. The anxious mother I am, I immediately sensed she was in danger and wanted to “save” her by putting her in her nest.

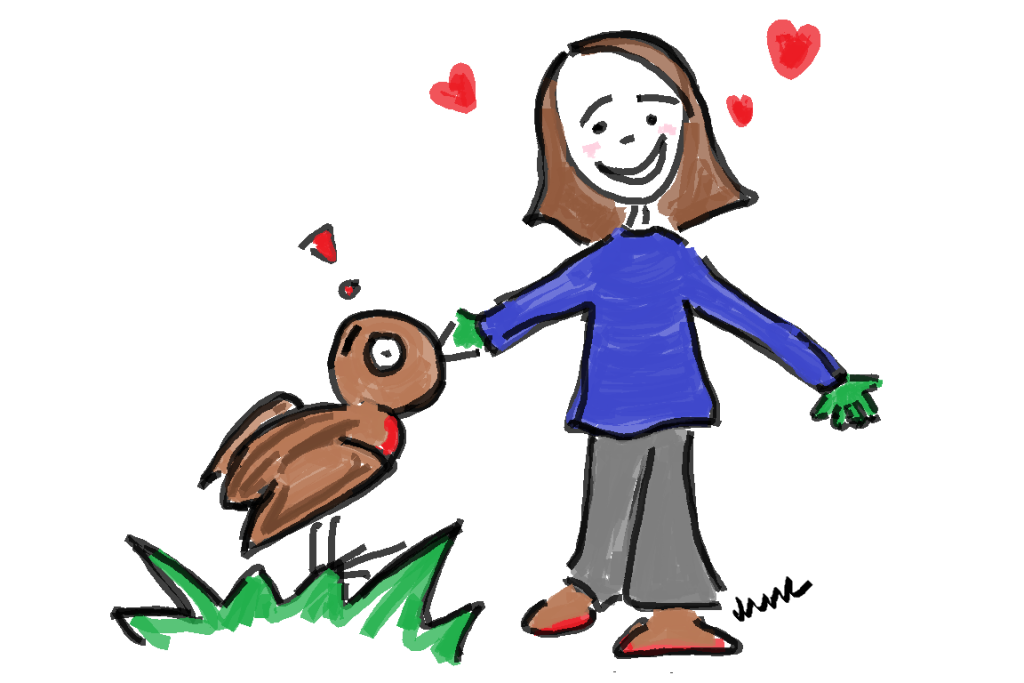

In my gardening gloves I reached out and said in my high, “for-baby” voice. “It’s okay, little birdie! I’ll help you!”

As I stepped closer, my face spread with a loving smile, the baby bird FREAKED. Its wings began wildly flapping and it tweeted hysterically. I gasped in surprise and immediately withdrew. What in the world? Why wouldn’t she let me help her?

I futilely watched her hop around for quite a while, fretting that she was destined for a cat’s lunch. But I couldn’t come up with a solution. Defeated, I left her hopping sweetly and obliviously among the shrubs.

As I reflected on this interaction, I had two thoughts. One is that animals are animals; I cannot interfere in her destiny. She has to brave the world as nature intended. Two, this interaction is a great example of how well-intentioned communications can be misinterpreted because of the lack of a shared meaning system. (I know… crazy bird lady. But bear with me).

I like to tell my students that we are like birds, born into little nests. As infants we have a very small world, or nest, that is our existence. Our experiences are limited, and what we experience we consider normal. It is the birthplace of our perception of the world.

Think of the book “Are You My Mother,” by PD Eastman.

Are You My Mother? (Beginner Books)

In the book a little bird is born while its mother is away looking for food. The bird immediately begins her quest to find her mother by leaving the nest and hopping away. On her journey she meets a cat, a dog, a plane… and each time she asks, “Are you my mother?” Each time the answer is no, until the end (spoiler alert!) when the mother returns, and confirms that yes, she is baby’s mother. So the baby bird learns that this is her mother (because she is told so) and the other creatures were not.

This is a great depiction of how we learn to understand our world. As little babies, we learn who are parents, friends, foes. We learn what is considered food. We learn what is normal, acceptable, and good. We learn how to behave, what to say, what not to say… And these are our normal.

One of the challenges in communication is that we all learn these things without consciously realizing we have learned them. And we learn them in unique, one-of-a-kind nests that are unlike anyone else’s. Our innate expectation is that everyone else has learned the exact same things we have and have the same default assumptions about the world. We expect that they follow the same rules. But this just isn’t true because it can’t be.

While we grew up in a certain kind of nest, with a certain kind of parent, in a distinct type of tree on a particular street, our communication partner also grew up but in a different set of circumstances and a different reality. Based on this, his/her communication and rules are different.

When communication interactions are tough, and you feel like you can’t understand why the other person is being unreasonable, it is good to pause and consider the nest in which the other person was raised. What was/is that world like? What rules apply there? How is your message being received in that context?

The goal in communication is to share meaning. Understanding the other and how he/she perceives the world goes a long way in helping us reach that goal. It allows us to frame our words and behaviors in ways that communicate our meaning so that our communication can be understood and ultimately we can reach our goal.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks